|

|

|

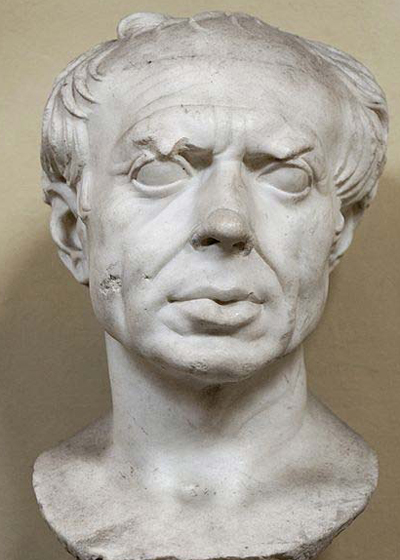

Gaius Marius |

|

|

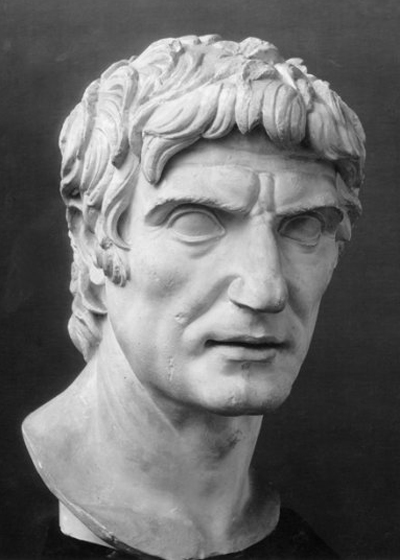

Lucius Cornelius Sulla |

I’m just finishing up a fascinating read in Mike Duncan’s The Storm Before the Storm, about the civil disruptions in the emerging Roman Empire from about 146 to 78 BC. Duncan’s thesis is that, before the Civil Wars that were chronicled by Julius Caesar, in which he most famously vied with Pompey the Great for control of the Republic, contention and animosity between the Senate and the urban populace, and between the Romans proper and their Italian allies, frayed and unraveled the civil order and sense of purpose that had made Rome such a success in the first place. Although Duncan cautions that one cannot always draw parallels between ancient history and modern times, the parallels are there and they are chilling for anyone with political sense.

This is the story of the Gracchi brothers, Gaius and Tiberius, who were reformers trying to help the landless peasants; of Gaius Marius, a “new man” from the Italian provinces who wanted to make his name in Rome; and Lucius Cornelius Sulla, a patrician playboy who found his footing as a soldier and politician. It is also the story of the factions—they were never so organized as our modern political parties—that coalesced around dominant men of the times: the “optimates,” who generally represented the best people, the patrician class, the Senate, the old guard, or in modern terms the one-percenters; and the “populares,” who represented the interests of the urban poor, landless peasants, ex-soldiers seeking a new livelihood, and others who wanted more than whatever they had—although the populare leaders were not generally from among the lower classes themselves.

If this all sounds familiar, it should.

Two themes emerge in Duncan’s telling of this story. One is that each generation of reformist leaders agitated for and succeeded in overturning elements of the mos maiorum, the unwritten rules of Roman civil order and government procedure that had operated from the earliest days of the Republic. These rules applied to such political business as the annual exchange of command between the outgoing and incoming consuls, the veto power and personal inviolability of the tribunes, and the process for originating laws in the popular Assembly with advice from the Senate. The Romans had always done things in a certain way, and it worked because everyone respected and followed the rules.

Just one example of the breakdown was in the career of Gaius Marius. As a new man from the Italian provinces, it was unusual enough for him to seek office in Rome. But he was elected consul—the supreme office of military and civil government, shared by two men at a time for a term of one year—on the strength of his military skill. Generally, the rules said that a consul who had completed his term could not serve again for another ten years—originally the law said for life—but Marius sought the office and was elected five times in succession for back-to-back terms.

The second theme is the gradual introduction of street violence as an answer to debate and unpopular votes in the Assembly. Tiberius Gracchi served as a tribune and was an advocate of agrarian reform—breaking up the large estates owned by wealthy citizens which had originally been carved out of public lands. When he was elected to the same office for a second term—another break with tradition—his opponents claimed he was trying to become a tyrant. His followers and opponents then engaged in a public riot, during which Tiberius was beaten to death in the Senate, and many of his followers were also killed. His brother Gaius was another reformer. When one of his opponents happened to be killed in a subsequent riot, the Senate decreed Gaius an enemy of the state who could be executed without trial. As a mob came to assassinate him, Gaius took his own life. This tradition of violence gradually accelerated from flash mobs and riots to the organization of mercenary street gangs who could be dispatched to deal with rival politicians and their followers.

At the risk of seeming alarmist—because, after all, the Roman Republic did fall into, first, civil war, and then into the imperium of the Caesars backed by their corralling of military force—I can see two parallels with our modern political situation. The first is the erosion of our own mos maiorum, or how we do things now.

When I was growing up—say, in the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations—we also had political factions and fights. But people could still respect each other. Democrats could speak well of Senator Everett Dirksen, or Republicans of Governor and later Ambassador Adlai Stevenson, even if they disagreed with their policies. And everyone played by the rules. Politicians running for office were expected to publish their tax returns, and they let their party take care of the political war chest and funding of their campaigns. If they were wealthy, they put their assets in a blind trust as they entered office, so their decisions would be free from the taint of any conflicts of interest.

But while the Clintons, both Bill and Hillary, were in office we saw financial scandals: a cattle futures deal that made an extraordinary amount of money with the hint of impropriety regarding the trading laws; a land deal that fell apart with more impropriety in the banking laws; and finally a family foundation that was supposed to be doing charitable works but seems to have been a personal fund for political campaigns and a place to employ loyal operatives between their service in government posts. None of this was clearly illegal—although an alert prosecutor could probably have made a case—but pursuing these ventures while one partner or the other was in public office clearly violated the traditional separation between money and politics.

Democrats and the appointed public servants in the Department of Justice who supported their policies turned a blind eye to all this. After all, why bite the hand of people who are doing such good works when the case is not entirely clear?

The trouble with this attitude is that eventually the tide turns and by then you’ve already established a precedent. When Donald Trump was running for office, people expected him to publish his tax returns but he never did. When he was elected president, people expected him to put his real-estate and branding empire into a blind trust, and instead he turned it over to his family members, who themselves were to become part of his administration. The notion that personal money and public office should be kept separate had gone out the window. And the only people who could prosecute in the name of the unwritten rules about tax returns and blind trusts had been politically removed from the levers of power.

A friend of mine says that one of the problems with the Roman Republic’s system of government was its lack of a separate police power. No established institutions of public prosecutors and guardians of the peace existed to defend the law when an individual or faction broke it. The Romans left prosecution to opposition politicians, who could take action or not depending on the political winds. By suborning the Department of Justice and the FBI on a federal level, and county prosecutors and police on a local level, our modern political system has achieved much the same end. We all watch the mad circus pass through and trash our unwritten laws with nobody to stand in the middle of the road holding up a hand to stop the parade and punish the offenders.

The second parallel with today’s political scene concerns mob violence. We’ve had political leaders, mostly presidents, assassinated over the years: James Garfield, William McKinley, John Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., Robert Kennedy, and the attempted assassinations of Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan. But these were individual acts of violence and sometimes of madness. They may have served political ends, but they were not—or could not be proven as—the policy of any group or party.

During the late 1960s, and again after the 2016 election, we have seen public protests break down into riots and mob violence. So far, most of the action has occurred on university campuses and been oriented toward issues of hate speech and unacceptable ideas. And so far, no one has been targeted for assassination or even accidentally killed. But, like the Clinton Foundation and the Trump assets, this politically directed violence sets a precedent. It may start with a riot on campus to silence and prevent a speaker who has the wrong ideas. It could eventually lead to violence in the streets to protest unpopular policies, as the Vietnam War and Civil Rights Act inspired street protests in the 1960s. This same brand of directed violence put the Nazis in power in Germany in the 1930s. I have always believed it could not happen here, but now I am not so sure.

As a thinking person with a center-right point of view, I am conscious of our American traditions, our own unwritten rules, and our sense of public civility—of treating people who act decently with respect, regardless of their politics. I would hate to see those traditions eroded to the point at which civil war might break out, because—aside from the public disruption, property damage, and loss of life—I fear what such a turning point might bring. As with the fall of the Roman Republic, a period of martial law or, worse, a personal dictatorship backed by military force might soon follow. And that will be bad for everyone who believes in a democratically elected representational government.

Something wicked this way comes.